Dave Kennedy, member of the Natural Arch and Bridge Society Board of Directors and former editor of its newsletter, SPAN, wrote this article about his trip to Rainbow Bridge for the publication Our Backyard in Glade Park, Colorado, September 6, 2017.

Lake Powell attracts a couple of million visitors to its blue waters and scenic red sandstone surroundings every year and about 100,000 of them make the trip to see Rainbow Bridge. This natural rock span, listed on Google Earth as the world’s largest natural bridge, though it is not, sits in Utah in a branch of Forbidding Canyon about 50 miles up-lake from Glen Canyon Dam.

The Natural Arch and Bridge Society has a page on their website at naturalarches.org which lists the “Big 19” arches and bridges in the world known to have a span greater than 200 feet. The Society seems to be the only body to set a protocol for measuring arches, which gets to be very technical for lay people. In short, span is defined by NABS as the horizontal extent of unsupported rock and is the organization’s basis for ranking the world’s arches and bridges. The Big 19 shows that Rainbow Bridge, spanning 234 feet, is the 6th longest natural bridge in the world and the 11th longest arch in the world (all natural bridges are arches, but not all natural arches are bridges). Its height is listed at 245 feet, making it also one of the tallest natural arches in the world. The five longest natural bridges listed in the Big 19 are all located in China. Of the Big 19, nine are located in China, nine on the Colorado Plateau and one is in the Sahara Desert of northeastern Chad, Africa.

In the NABS nomenclature, Rainbow Bridge is classified as a meander bridge formed in Navajo sandstone. That geologic stratum dates to the Jurassic Period from about 145 million years ago to about 200 million years ago. The bridge soars in a huge arc over the canyon and its intermittent stream below. The reaches of Bridge Canyon stand sentinel behind it and the entire scene is watched over by 10,000’ Navajo Mountain in the background. This is an outstanding example of the fabulous and fascinating landscapes of the American southwest.

President William Taft designated 160 acres that includes Rainbow Bridge as a National Monument in May 1910, less than a year after it was first documented by Anglos, though it could have been seen earlier by explorers who didn’t bother to record their having seen it. There is evidence of Native American habitation and visitation that dates to ancestral puebloan times and the bridge is held sacred by Navajos, Paiutes and today’s pueblo cultures. The native name for the bridge translates to “rainbow turned to stone.”

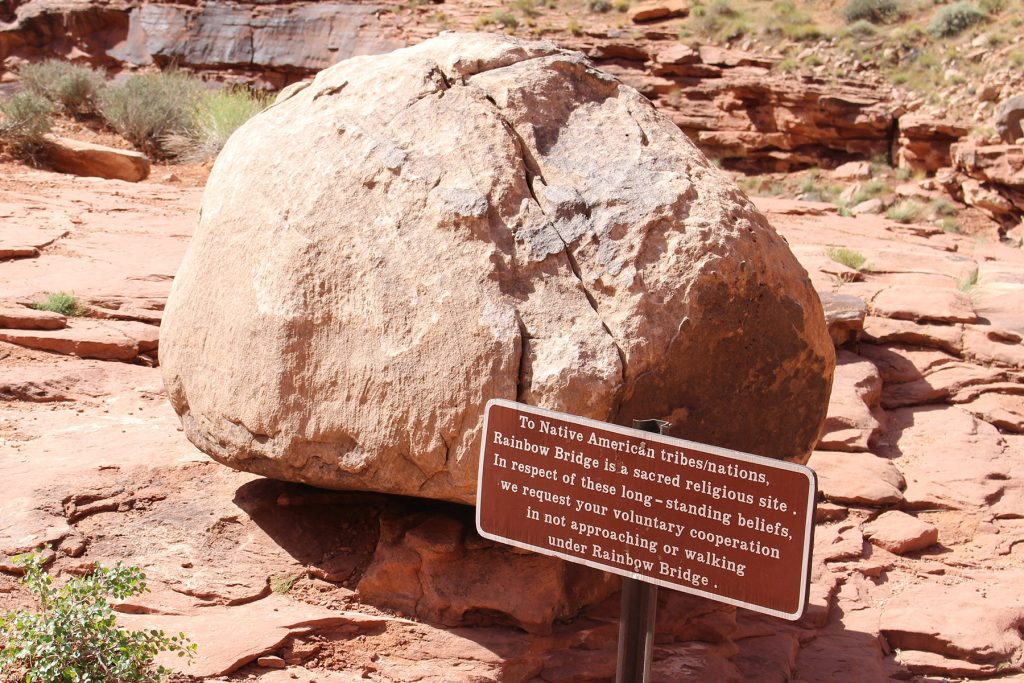

The native religious reverence for Rainbow Bridge has generated controversy over the years, which has been resolved to no one’s complete satisfaction by the placement of boulders and signs to discourage visitors from approaching or walking under the bridge. The National Park Service asks visitors to respect the site’s traditional religious nature by not doing so, but a lawsuit in prior years established that the NPS may not ban people from going under the bridge and that the current voluntary request does not constitute a ban.

Another controversy surrounding Rainbow Bridge comes from the story of its Anglo discovery. Two parties had been trying for a few years to locate the bridge based on tales told by Native Americans. One was led by Byron Cummings, a dean at the University of Utah and another by John Wetherill, he of the famous Wetherills that discovered Mesa Verde. At length the two parties combined for the trip that led to the finding of the bridge in 1909. Heated arguments ensued as to whether the discoverer should be Cummings or Wetherill. At least one source lists them in an epic weasel-out as co-discoverers.

Other controversies involving this natural bridge include scientific values, access, protection and cultural significance, all of which have shifted over time and are probably still shifting today.

There are two official ways to get to Rainbow Bridge National Monument. You can take a boat or you can hoof it. Private boats are allowed to enter Forbidding Canyon and tie up at the courtesy dock at the trail head for the bridge. The dock has a restroom but no other services are to be had there. Commercial boats are run by the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area concessionaire from Wahweap Marina. Trips take all day and, at the time we went, cost $125 per person.

The distance of walk from the dock to Rainbow Bridge depends on the level of Lake Powell. When we went the walk was about 1.25 miles each way. The trail ends at a viewing area near the bridge and there are signs requesting that visitors respect traditional religions and do not approach or walk under it. The concessionaire staffer on our trip yelled at one tourist to return to the viewing area and not go farther.

The boat ride is about two hours each way and leaves Wahweap Bay on the way to skirting Antelope Island on the 50-mile trip up-lake. Warm Creek Bay and Padre Bay, Lake Powell’s largest bay, offer up their fantastic scenery along the way.

The tour travels by several good viewpoints of Tower Butte which was a landmark for travelers long before the reservoir came into being.

Observant passengers may see other small arches in the sandstone shoreline of the lake and photo opportunities abound.

Not long after the boat enters Forbidding Canyon, 25-foot Rainbow Canyon Jughandle arch comes into view high on the right.

The blue water contrasting with the sandstone canyon walls make the entire trip a photographer’s paradise. Online information about the tours and reservations can be found at lakepowell.com.

The other official way to get to Rainbow Bridge is to hike from Navajo Mountain by way of either of two long trails. The northern route is 32.7 miles roundtrip and involves about 7000 feet of elevation change. It has the advantage of being less steep, though harder to get to, and it also goes near lovely Owl Bridge. Its 61-foot span will have you digging your camera out of your backpack.

The southern trail from Navajo Mountain is shorter at 24.5 miles roundtrip but much steeper, with over 8400 feet of elevation change. Distances and elevations for both trails are taken from the alltrails.com website.

Both trails are entirely within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation except for the little distance they are in Rainbow Bridge National Monument. As such, permits from the Navajo are required and can be obtained from the Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation Department in Window Rock, Arizona (928-871-6647) or from their website at navajonationparks.org.

Hikers with shuttle capabilities could walk in on one trail and back the other, and by making prior arrangements with the concessionaire at Wahweap Marina, hikers can ride out on one of the boat tours to the marina.

The trails are not maintained and may be subject to flash flooding, hot, dry conditions in the summer and severe cold and wind in the winter. There are not many trail signs but the trails are mostly marked with small stone cairns. These routes are not recommended for inexperienced or casual hikers.

The Lake Powell area of Utah and Arizona envelops a treasure trove of nature’s wonders for visitors of all interest levels from the casual to the intrepid. Visiting Rainbow Bridge will surely be one of the highlights of anyone’s trip to the area.

Did this Arch really fall? Read in NABS news letter that a Rainbow Arch fell. But picture didn’t look familiar???

No, Rainbow Bridge did not fall. The Rainbow Arch that fell was a small arch in Arches National Park. Details here:

http://www.naturalarches.org/blog/arch-collapse-in-arches-national-park-rainbow-arch/

When I was there in 2012, a Nation Park Service ranger thanked us for our “voluntary” compliance with Navajo request not to walk under bridge, then led us on trail under it at someone’s request (not mine).

I am one of the many who think that Lake Powell hides, not shows, the beauty of the desert, and though I enjoyed the boat ride, and it did make pictures, I found the lake itself to be out of place and unnatural, and I regard the “bathtub ring” created by previous water levels as damage to the desert in the same way I regard graffiti as damage.

I enjoy this site, and appreciate your work.