|

|

|

Natural Arches of Tassili National Park |

JOURNAL OF 2006 NABS JOURNEY TO ALGERIAby Stephen C. Jett

with photos by Alene Watson (48 photos), Lola Petermann (9 photos), Map of NABS Feb 20-25 Tassili Plateau itinerary (PDF, 1.1 MB)

Feb. 18, Paris It was drizzling this morning, and after a bad night for sleep, Lisa and I stayed in the apartment most of the day, emerging to do some errands. At 7:00 P.M., a taxi picked us up and took us to Orly Airport, where we ate a sandwich and waited for the Aigle Azur flight to Algeria, which was half an hour or so late. I identified some potential Natural Arch and Bridge Society members and spoke with them. They were, indeed, participants. The flight, originally scheduled for 10:00 P.M., took off around 11:45, and we were served dinner about midnight. Day 1: Feb. 19, Djanet, Algeria The plane landed around 4:00 A.M., and we were met by our sleepless trip leader Guilain Debossens. Formalities took up to first light. The passage through customs was less than efficient. The waiting-room wasn’t large enough to accommodate but about half the passengers, the other half being left in line outside in the 52° cold. From the waiting room, the line passed through a short corridor with two passport inspection stations on the left side but hardly enough room for one person to pass the first station to reach the second one. In the airport lobby was a large painting of the hoax Egyptian-style Tassili rock paintings. Finally, we all made it through and then piled into a big van and were driven some 20 miles across a barren, sand-veneered, Pleistocene lake bed. Scattered hills and small mountains came nearer, and we saw both exfoliation domes of weathered granite and outcroppings of what was probably heavily patinated sandstone; some eminences were studded with standing rocks. The highway entered the hills and came to a broad wadi (wash) flanked by a low stone dike. Outside of the dike were innumerable date palms and tamarisks and garden plots protected by waist-high fences of vertical palm fronds and tamarisk boughs. Djanet, a town of about 15,000 inhabitants [Descotes-Toyosaki 2006], lies where another wadi conjoins the first, and sprawls up some of the lower slopes. Buildings are of stone or cinderblock and have flat roofs. There are some small hotels, ours, the Auberge des Ajjers, being the best. It is in the white-stuccoed one-time barracks of the old French Foreign Legion Fort Charlet up a considerable hillslope from the center of town. On the ridge crest immediately above is the vacation home of the Algerian president, and the little fort itself lies a bit farther along the ridge.

Breakfast was served on a long communal table in the "restaurant," and we were offered cookies, ersatz butter, jam, and tea or lava-like coffee. When one or two deemed this inadequate, some poor-quality French bread and tap water were added. Alex Ranney became quite concerned that we would be inadequately fed on the trip, he being very thin and wanting to fight excessive weight loss. He began to think we might be on "concentration-camp" fare. Guilain assured him that food would be copious.

After breakfast, people were assigned rooms in an adjacent building (except ours, No. 8, was not yet ready). Most rooms accommodated two, in simple single beds, but Lola Petermann, Alene Watson, and Barbara Green, all from Salt Lake City, were given a room with four beds, as were Peter and Dagmar Schaefer, a nice couple from near Frankfurt, Germany. The building floors are of paint-bespattered concrete. Ceilings are high—ours has a brown-stained patch about the size of a bed, reflecting what we assume is a past leak in the roof. A bare bulb hangs down. Our room is a corner one, so we have two barred windows. The toilet in the building has no seat, and the flushing mechanism doesn’t work. You have to fill a plastic bucket from a wall tap and pour it into the bowl. An open window gives out onto the terrace. If you don’t like this option, there is also a large lavatory comprised of multiple booths with squat toilets —also requiring pail-sloshing. Some of the room doors stick or don’t close properly, but there are real French casement windows with long curtains. The view from the esplanade is a sweeping one, of the bare dark hills, the orange-sand wadis with their floodplain date orchards, and Djanet. From below comes the bleating of goats. The ground was damp from a recent rain, which, Guilain’s friend and assistant Daniel Putelat told me, was a good thing, because up until it fell, there had been a sirocco and the air had been so dusty that photography was impossible. Our first need after breakfast was changing dollars and euros to Algerian dinars. Accordingly, we descended the hill via a long set of broad stairs and reached the main road. A short walk past shops and a small hospital brought us to the little local branch of the Banque d’Algérie. The bank was supposed to open at 9:00 A.M., but the steel front doors were not, in fact, unlatched until about 9:15. Inside was a long, narrow counter topped with chipped and pitted marble and, at its right end, a wooden cabinet where the Black guichier sat. Behind the counter were two men, utter contrasts to one another. At the right-hand end was a humorless, stony-faced, mustache-wearing fellow who could have been one of Saddam Hussein’s doubles—the resemblance was striking. He, with occasional gestures and ejaculations of boredom or disgust, served a series of local clients. Currency exchange was handled at the counter’s left-hand end, by Hakkim, a very skinny Arab with a high forehead and fairly severe nervous habits of oscillating his head up and down and flashing peculiar grins while rolling his eyes up at you from under his brows. Unlike the other employees, who dressed casually, he wore a pinstriped gray suit with a necktie. The paperwork involved in changing euros or dollars into dinars took a long time for our group of nine and required me to do a lot of interpreting in French and even doing some algebra to work out equivalences in the three currencies. At one point, a Black man took Hakkim’s place but had to call the latter back for consultations from time to time. A bit later, a Tuareg man brought in a ledger of some kind and gave it to Hakkim’s replacement, which inspired the latter to chew out Saddam at some length—perhaps the latter had left or dropped the thing outside. There was an office area to the left of the counter, and a 40-something woman emerged and pleasantly told us, in French, that she had spent time in the United States as one of a group of Arab women, presumably studying banking, in Washington, D.C., Detroit, Chicago, etc. She seemed too sophisticated for this backwater branch. Everyone in our group had cash to exchange except Alex, who had traveler’s checks. To cash traveler’s checks in the amount of €400, the banker required proof of purchase, which Alex had left in his room—so, he was obliged to go back up the hill and then come down again. Thus, he was last in line. At a later point, he thought he was being short-changed and ran outside where the rest of us were waiting, in order to get help. It turned out to be a misunderstanding. But the exchange fees for traveler's checks were unexpectedly high and he ended up with less cash than he really needed for his first week’s costs (he was holding off on committing to the second week until he saw what the first week’s food would be like). When at last we were done, we went a few buildings down the street to the ONAT travel office, where we went through the prolonged process of handing over 72,420 dinars to pay for our trip to the Tassili (75 d.a. = $1.00). A Tuareg man in full costume photocopied our currency declarations, although the tabletop machine did not work properly; sometimes the paper feed had to be opened and closed to get it to accept the individual sheets of paper he fed into it. Alex, being cash short, was allowed to agree to supply the balance at a later date. Out on the street, a good percentage of the men were in Tuareg (Tamahaq) traditional costume: a bulky white, black, or dark-blue wrap-around headcloth (chèche), in most cases covering the mouth and imparting what could be construed as a slightly sinister look; and a shoulder-to-toe caftan in one color—light green, gold, white, bright blue, even pink—of plain or brocaded fabric, often with a bit of embroidery bordering the neck opening and slit below it. There is a matching pair of loose trousers. The men wear commercial sandals or athletic shoes. A number had cell phones (there are no land lines to Djanet).

For the most part, the Tuareg are very tall, many gracile but a few robust—although there is the occasional short, wizened male. We saw only a few women in the street, some in full-length black and completely veiled, some not; one wore saffron orange. Arabs criticize Tuareg women for going unveiled. Racially, the Tuareg appear to be basically Black/Nilotic, although some are somewhat lighter-skinned. They tend to be quite dignified and imposing but smile easily and often embrace four times when greeting. After looking into a crafts shop, we returned to the hotel for a 1:00 lunch: omelets, French fries, crudités, decent bread, canned red tuna, yoghurt. Having essentially been awake continuously for about 30 hours, we allowed ourselves a couple of hours of rest in our rooms during the afternoon. After walking up toward the old fort and taking a few photos of the town and hills in the late light, at 6:00 Guilain and Daniel led us down the stairs, through the Arab market—small food shops and stands (and a "Tayota" garage to service the numerous Land Cruisers). I bought a rug book in a book-and-souvenir shop. We went on to the shantytown-like African market (marchée du oued), but it had pretty much closed down for the day. So, back to the room (passing the goat pen whence we had heard baaing) to rest before 8:00 dinner. The latter featured mutton couscous. Day 2: Feb. 20, Tassili N’Ajjer We were awakened at 5:15, breakfasted at 5:30, and left in three vans a little after 6:00. The vans stopped at a small bakery and the drivers stacked bare baguettes in the back end like firewood. As the about-to-rise sun painted wisps of cloud salmon against a turquoise sky, with the crags silhouetted in front, our Tuareg driver conducted us with élan up a wide wadi ten miles to the base of the Tassili escarpment, where we found our 18-animal donkey train ready to load up our equipment; they had already loaded most of the water containers and supplies. There was a grove of acacias up the wadi.

After a little while, we put on our day packs and walked a little farther up the road to where the trail starts up a talus of rotting granite boulders. It rises to a saddle, then flattens out for a while. Going along led us through another gap into a long, monumental gorge, undoubtedly fault-controlled. We entered well above the bottom, and we could look down into a slot inner gorge with a pool, taking the drainage out of this trench, which is called Akba [Canyon] Tafilalet.

We descended and then walked up canyon. There were some desert shrubs, including a few composites with saffron flowers and another kind with thorns and violet blooms. While we were ambling along, a file of white-turbaned small Black men overtook and passed us, walking along briskly, with small packs and carrying water containers. One of the guides told me that they were from Niger and were clandestinely traveling to Libya to find work. After hiking quite a way toward the canyon head, we climbed out on the opposite side via a cheminée, or what I would call a couloir, up talus and bedrock, passing a good-sized rock tank full of water. At the top, we came out on a broad, low-relief plateau, its surface being bedrock and thousands of loose stones (this is called the Reg). Our vertical distance gained was about 400 meters [1,300 feet]. After a short rest and lunch, we headed across the Reg, but taking time to make a short detour to where, in a wadi, an enormous cypress was growing—five to six feet in diameter. There were others some distance up the wadi. [Cupressus dupreziana, or tarout, of which these may be the last wild specimens, was once common in the central Saharan highlands (Lhote 1959:49).]

We tramped over to another ragged sandstone escarpment bounding the stripped surface of the Reg and proceeded to Tamrit Camp, arriving about 2:00. At 3:15 or so, Daniel and the Tuareg guide Mohamed Bilali led us for about 45 minutes to Tan-Zoumaïtak ("Big Horn"), a cliff shelter containing some well-known polychrome rock art: apparent dancers, mothers with children, a mouflon, an ibex, a possible gnu, a weird and unidentifiable creature, etc. Daniel took a couple of us a little way farther, to odd little Curious Arch (ALG-145), free-standing and with one quite thin columnar pillar. The opening is 3.3 meters (10.8 feet) high. Elsewhere, we saw an arch atop a lump of rock and Elephant Rock (ALG-9), a free-standing arch with an opening height of 1.9 meters (6.2 feet). On the way back, Mohamed led us to an overlook of the upper end of the Great Canyon of Tamrit, the area’s deepest (200 meters/660 feet). It was indeed narrow and deep, reminiscent of Colorado’s Royal Gorge. Lisa and I set up our tent some distance away from the others, in front of a small cliff. The Tuareg guides cooked dinner, in part on a small fire made with two long sticks of acacia wood that they would push farther into the fire as the ends were consumed, and they fanned it vigorously to ignite the new parts. For themselves, they made up a big roundel of wheat-flour-dusted semolina dough, put it on the hot sand, and buried it in the coals; the resulting bread is called tadjila. We all had soup, but the tourists were given French-style bread. Dessert was dates.

After supper, the Tuaregs got around the fire and sang, with great verve and much clapping,

gesturing, and occasionally individual dancing. They played with the veil parts of their head

cloths, repeatedly rearranging them. Two fellows drummed rhythmically with their hands on

five-gallon plastic water canisters. One man would call out a verse line and then the others would

belt out a chorus line. We learned that at least one of the songs was for a wedding celebration.

The singing seemed much more African than Middle Eastern. They sang perhaps half a dozen numbers.

The tadjila-bread-making procedure is to put the semolina flour with a little ordinary flour for adhesion into a metal bowl, throw in a measure of salt, pour in some water, and mix with the fingers. Kneading is done by pushing hard and vigorously on the dough ball with the fists. The edges of the roundel are pulled up and to the middle and then kneaded in. When the dough is ready, the coals are brushed away from the hearth, the hot sand is smoothed out, a little flour is sprinkled on it and on the top side of the dough, the dough roundel is laid on the smoothed sand, more sand is shoved atop the loaf, and the coals are swept onto the sand. Half way through the baking, the loaf is uncovered, turned over, and reburied. When the bread is done, it is scraped and rubbed to remove ash and sand. When the Tuareg men have their chèches over their mouths, their speech is muffled. The night sky was absolutely incredible, with more stars than anyone from light-polluted places could imagine—breathtaking. The stars sparkle hardly at all. During the night, a wind came up and there was much flapping of the outer part of the tent. I slept badly. Daniel and Guilain have their own preferred guides. One is the guide Mohamed Bilali, a slender, sweet older Tuareg, age 64 [his photograph appears in Cailleux 2006:41]. He works for ONAT on a piece-work basis only, and they haven’t paid him for months. He was reluctant to come along, for that reason, but agreed out of friendship for Guilain. Their other regular, the head donkey-driver, is Mohamed Touggui, a younger, shorter fellow with a slightly simple demeanor. The agency assigned, in addition, Mohamed Akhnini Atouat to keep tabs on things. Akhnini is quite tall and thin and has the typical graceful, deliberate, slightly swinging stride of the Tuareg. He adorns himself most of the time in an indigo-dyed (chèche) that has a striking sheen in the sunlight. He also applies blue coloring to his somewhat graying hair and his facial skin. He uses a hand mirror to get his “look” right. Yet on occasion, as at meals, he appears bare-headed and in a fashionable shirt. Another of the Tuareg staff sports a different native outfit every day.

Akhnini is quite a sophisticated fellow. He speaks French well, softly and suavely, and knows a good deal about the world. We talked about a number of things, including Islamicists (intégristes), whom he says are anti-religious. Recruiters, especially Saudis, indoctrinate young men, telling them that they (the recruiters) will teach them (the recruits) real Islam. Akhnini counsels young men not to listen to such claims. He says to garner votes, all the political parties, of whatever persuasion, tack “Islam” onto their names. In the days when Libya was being embargoed and Algeria had a very leftist government, the latter prevented importation of electrical appliances from capitalist Japan, etc., but subsidized foodstuffs so that prices of them were very low. As a result, Tuaregs began smuggling appliances in from Libya and food from Algeria into Libya. There are still some pastoralists on the plateau, but most moved to Djanet after desiccation drove them and their animals out and post-independence establishment of public housing and schooling drew them to the settlement. Tourism is now the economic mainstay and the only thing that keeps most Tuaregs knowledgeable about the Tassili. There is still some polygamy. Formerly, plural wives all lived in harmony in one house, but today they are not content to do so and want their own places. To have multiple wives today is to have problems. (Apparently, Akhnini has two spouses.) Akhnini has three children: 10, 7, and 3. TV is state-controlled in Algeria, but people can pick up anything from satellites and the government does nothing to curb that. Our Tuareg personnel consists of: guide, Mohamed Bilali; chief donkey-driver, Mohamed Touggui; ONAT representative, Mohamed Akhnini Atouat; cook, Ibba Mukhtar; assistant cook, Ibba Mokhtar; other donkey drivers and cooks, Méchar Moussa, Wawani Salah, Hamid el-Housseini, Yousefi Mokhtar. Some of the guides, notably Mohamed, pray on occasion, chanting prayer in the evening. Day 3: Feb. 21, Tassili N’Ajjer In making tea, water with tea leaves in it is heated in a small teapot, a lot of sugar is thrown in, and the liquid is poured back and forth between the pot and another container, raising the upper container until the stream is two feet long, and then lowering the upper container until the stream is minimal. Foam develops on the surface.

After bread and tea for breakfast, we set out, initially on the route we’d taken to the rock art, over a broad stripped surface with jagged escarpments on either side [see Tamrit Panoramic Photo, taken by NABS member Tom Budlong on a previous trip, which shows the donkey trail to In-Itinen in the upper Tamrit area]. In the Tin-Itinen area, Guilain led us to a quite large opening (ca. 20 meters/65 feet high) called Takouba ("Sword") Arch (ALG-75). This is Ray Millar's favorite arch in the whole world! It is in a projection of rock and has a thin outer buttress. Not far away is a large pedestal rock high above, and there are tall rock columns. We also visited Irrekam Arch (ALG-76), Figurine Arch (ALG-80), and Pendulum Arch (ALG-81).

The sandstone in the Stone Forest is arkosic and basically ashy-white. Weathering causes a rusty cortex to develop, so that the rock surface takes on an orangish-buff color, characteristic under the overhangs. On exposed surfaces, a dirty patina develops, deepening into black on those that are most exposed and subject to wetting. This thin patina is presumably organic in origin. There are also some limonitic concretions in the rock.

The rock has numerous bedding planes, joints, and other vertical fissures—perhaps shrinkage

fractures—so that the upper parts of cliffs and mounds have been etched into a knobby surface

dubbed “elephant skin.” Rainwater running down from the upper parts dampening the lower

parts, plus, probably, groundwater wicking, has led to the cliff bases being gradually sapped until

they have been much undercut, creating overhangs and in many, many places penetrating fins of rock

and making natural arches. The whole line of this kind of country, a dissected escarpment that runs

for 50 kilometers (30 miles), is known as the "Stone Forest." It must be one of the

world’s most bizarre landscapes, with its fins, pinnacles, overhangs, "gargoyles,"

uncounted rimrock openings and minor ground-level arches. There are curved cones that look like

Hindu temples, and columns resembling stalagmites. Some of the columns, being undercut, have

toppled, leaving drums and circular sheaves of vertical strata strung out along the ground as if

some Saharan Sampson had brought down the temple. There is a definite joint-controlled linearity to

the landforms, but there are numerous gaps in the fins and in many places rock columns have been

isolated and rounded by weathering and stand like clusters of candles. We saw so many arches that

we arch-fiends became blasé, just glancing at many an opening that would have demanded our

full attention had it been in Utah or Arizona.

Our group includes a good percentage of older people. Alex, age 71, had polio when 19 and has only about 50 percent breathing capacity. Alene Watson is six times a great grandmother. All are experienced hikers, but Guilain and Daniel, in consultation with the guides, decided to take something of a shortcut. We went up toward Tiferas N’Elias but headed off across a long flat, partly on a defunct 4-wheel-drive track used by Henri Lhote in the ’50s [see Lhote 1959]. His camp, Ouan Lhote, was off to one side. We walked through a little gap in the sandstone, and I noticed on the far side some pecked inscriptions in Tifinagh writing. We arrived at Tin Aboteka, where we expected to have lunch, but the donkey train did not arrive [see Tom Budlong's Tin Aboteka Panoramic Photo taken on a previous trip]. We looked around—there were some nice columnar pinnacles—and waited. It turned out that the train had gone to an alternative site, so we hiked through a pass, with arches on either hand [Frame Arch (ALG-178) and Square Arch (ALG-179)], and to the other camp, where we lunched on an elaborate salad and bread.

Later in the afternoon, there was an arch expedition to the In-Etouami area. A fairly straight walk across the Tin-Tazarift West area led us to several openings. One fin had so many basal openings that it was like Swiss cheese. We saw Bouhan ("Owl") Arch (ALG-16). There was Moula-Moula Arch (ALG-17), in a mound of rock. There was a basal arch with a very thin column (ALG-19). There was Oudad Arch (ALG-20), a free-standing one. We also saw "Whole String Arches" (ALG-21, ALG-22, and ALG-23), Tafuk Arch (ALG-188), and Triptych Arch (ALG-389). One opening, Tadeft Arch (ALG-187), was in a camel-shaped free-standing mound of rock. In-Etouami or "Surprise" Arch (ALG-390) was in a thin fin; a group photo was taken there. Nearby was small "Big Eye" (ALG-391), through which one could photograph "Surprise." A small unnamed arch was a bit further away (ALG-392). The last arch was "Indentation Arch" (ALG-393), from whose apex a large, square chunk had fallen, leaving a square-topped opening.

Water is transported in black-plastic containers. In addition, at the campsites, a goat water-skin is hung on a cliff. It’s covered with long, black hair.

After dinner in the evening, the Tuaregs sang again. Lisa and I set up our tent in a sandy wash a bit away from the others. There was a beautiful sunset.

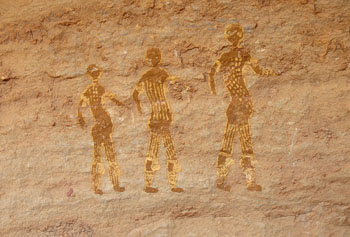

Here and there, we see little semicircular dry-masonry structures against cliff bases, open-roofed for the most part but somewhat corbeled inward at the top. These were enclosures for young kids, sheltering them from the wind. There are also other, larger stone enclosures for trash disposal and collection. Unfortunately, more trash seems to be casually discarded than accumulated in the designated structures. I have seen several species of birds. For some, I did not observe any distinctive field marks. One small bird has a black front half and a white rear half; it is called a moula-moula, locally. There is a larger black bird with a white cap and some other white parts. There is a small bird with a ruddy body and gray cheeks with an eye stripe. There are pigeons, swallows (at the canyon), raven-like corvids, and black buzzards. There are also lizards and dull-bluish beetles with very long legs, plus a few large grasshoppers. There are lots of mud-dauber nests. One morning, at Tamrit, I saw a small, furry animal like a pint-sized groundhog scurry across the rocks. It could have been a hyrax. We have seen tracks of fennec, sand cat, and jerboa. Day 4: Feb. 22, Tassili N’Ajjer We walked a modest distance during the morning, looking at rock art. Much of this was from the Round-Heads period; there are large warrior figures with what appear to be globular helmets. We also saw the well-known image, in red, of a crescent-shaped, presumably bulrush-bundle boat.

The arches for the day included a very nice ground-level arch, Graceful Arch (ALG-35). Nearby were ALG-36, ALG-37, ALG-38, ALG-39, and ALG-40.

The afternoon was consecrated to resting. I worked on the journal. Lisa and I selected a separate tent site, near a little bowl-shaped, room-sized basin in the rock, which had a small arch next to the notch that gave access to it. We sat in there, reading and writing. After supper, David Parker showed us the zodiacal light looming in the west. The stars were "over the top." We were in the sleeping-bags before 9:00. Day 5: Feb. 23, Tassili N’Ajjer At the beginning of the day’s hike, we visited a place where three parallel fins of rock are each pierced by an arch, the three all in line. There is a low one, a second called Izem ("Gazelle") Arch (ALG-47), and a third called Abareqqa ("Trail") (ALG-46) because the trail passes through it. A bit later, we saw the irregular opening of "Bonus Arch" (ALG-48), "Skyline Window" (ALG-144), and "Notch Arch" (ALG-55), among many lesser ones.

At one point, hiking across a stripped surface, we passed a rock-covered mound perhaps 15 feet in diameter and three feet high. Akhnini said that it was a prehistoric family tumulus, built by ancestral Tuaregs, whom he said were "giants". The people were buried with their jewelry. We came to a place where a slot canyon came out, up which ran a dark pool of clear water. The drainage traversed the cross valley and entered another fault slit; there was a pool some way down it, as well. These desert pools are called guelta. We dipped out some water and rinsed a bit. Then, back to the camp for lunch, another fancy salad.

Our morning destination was the Séfar rock-art area. Our first panel was in a narrow corridor and consisted of amazingly dynamic small red figures holding graceful bows and representing sprinting hunters (or warriors) giving chase.

There was also the famous Great God of the Tassili, a very large white figure around which other, smaller figures with upraised hands are disposed. To the right is a giant mouflon. There were various other panels, some with small red cattle, human figures, and so forth. "Tassili" apparently refers to shady rock overhangs; N’Ajjer is, correctly, N’Azguer ("Of the Bull"). [Lhote (1959:40) refers to the fine style featuring cattle as Bovidian Period; he says that "Tassili" means "Plateau of the Rivers".] Lisa and I visited the resting donkeys. One had a brand: #. Donkeys are called by shouting "Eo-ha-ha-ha." Donkey pack saddles are made of a pair of bent sticks, most of whose lengths are set a foot or so apart but whose up-curving ends are bound together with rawhide strips, sometimes with a small reinforcing cross brace. A strap loops from the posterior end and goes under the base of the donkey’s tail. Some use green-plastic rope, some round rope plaited of strips of cloth. On one saddle was the vestige of the original tail strap, a 1.75-inch-wide braided-goat-hair strap. A rope goes under the animal, just behind the forelegs, and some saddles also have another rope running across the animal’s chest at the base of the neck. We camped at a well-frequented spot, ate lunch, rested, and then went for a rock-art tour. Most of the pictographs were in the delicate red-figure style (although certain other colors were also used: yellow ochre, cream, sepia). There were human figures, cattle, wild animals, huts, and one bulrush-bundle boat.

A smugglers’ route passes through Séfar, and we are advised to keep our valuables at the campsite. David’s tent has an electrostatic attraction to sand, and it has become covered with grit. Ahmoud Machar, one of the personnel, lent Steven Negler a fancy tooled-leather Tuareg neck purse to wear during the trek. The country is, apparently, crossed by two sets of parallel major joints or faults, at right angles to each other. Joint/fault-controlled erosion has resulted in the development of long, rough-walled corridors and fissures intersecting every so many yards. We dined and went to bed before 9:00, without any singing. Day 6: Feb. 24, Tassili N’Ajjer The guides use two axes for cutting the firewood. One steel head is triangular, its point passing through the knobbed end of a natural-stick handle. The other is hafted on a stick that passes through a socket. Both look hand-forged. [I later saw an example of the first type at the forgeron’s (blacksmith’s) in Djanet.] Alex decided to conserve his strength today by riding one of the unburdened burros. The rest of us took off on foot with Daniel and Guilain into the Stone Forest to see some more arches down the cliff-bound corridors. One, with two adjacent stone towers, is called "The Castle" (ALG-426). Another has been dubbed "Avenue Arch" (ALG-101). At the junction of two corridors was a small but steep-sided mound of sand beautifully illuminated by sunlight and contrasting with the dark and shadowed rock. We hiked on and across a broad, rolling, stony surface until we came to our luncheon place, Tin Itinin, on the edge of the Stone Forest country. There were some Dromedary Period pictographs here, plus some nice but faint earlier paintings of cattle, a giraffe, and a cheetah pouncing on a cow. There was also some painted Tifinagh writing. Each of three different manifestations was in a different shade of red ocher. After eating and an hour’s rest, we started off again, across rolling, stony open country, passing a lonely Muslim grave with rough head and foot stones, eventually entering another part of the Stone Forest, with many long, enticing corridors and cross corridors and a multiplicity of improbable columns. One broad open area surrounded by pinnacles reminded one of Canyonland’s Chesler Park.

Guilain led us a short way off the trail to show us an unusual and impressive arch high in a free-standing monument. He climbed up into the opening. The feature is known as Allagh ("Spear") Arch (ALG-77).

Ultimately, further hiking brought us back to the giant cypress at Oued Tamrit that we had seen prior to reaching camp on our first day. Here, we unloaded and set up our tents. Along the way, a small group went to see Dinosaur Arch (ALG-7).

Lisa and I picked a spot in the wash upstream from the tree, and then took a walk further up to photograph a second huge cypress and the donkeys, which were browsing on the numerous small shrubs flanking the wadi. Another large cypress was visible farther up. We saw a few exotic-looking tall shrubs in the washes, with big, leathery leaves. There were also occasional oleanders. Mohamed Bilali says that if you get the leaves on your eyes, you will loose your sight. According to Daniel, Mohamed has eight children, by a first wife and the present wife. The oldest son is 30 and a camel owner/driver. He’s unmarried because the bride price is a camel, and giving his away would put him out of work. When there is a divorce, the man leaves and the woman keeps the tent and furnishings. She can remarry. Dinner was served around a fire within a chest-high circular enclosure of dry stone masonry. We all went to bed early to get rested for the long hike the next day. Day 7: Feb. 25, Tassili N’Ajjer and Djanet There was some haze in the air this morning, apparently reflecting a sandstorm in the lower country. It thickened as the day went on. Alex rode a donkey and the rest of us hiked across stony country for miles. Shortly before reaching Tafilalet canyon, Guilain showed us a double arch, "Nutcracker Arch" (ALG-70). When we reached Tafalelet, instead of descending the cheminée we headed the branch and came down into it via a very stony left-bank trail. From this point, we retraced our earlier route, proceeding down canyon, largely on the talus slope. The view backward was unreal, a sort of Maxfield Parrish rocky background of soaring cliffs and crags. The texture of the canyon walls was reminiscent of Havasu Canyon. Across canyon, we spotted two tourists and two guides on the ledge overlooking the slot canyon. The trail went steeply upward and then zigzagged downward into the main canyon with its broad wadi. We marched down that until we reached the mouth and the vehicles that had come to fetch us. The donkeymen and other non-guiding staff were all there and saluted us for having made it. Back at the auberge in Djanet, the hôtelier’s son-in-law had failed to pass on the word that we were expected for lunch, so the cooks had to scrounge up what they could in the kitchen. They did pretty well: salad, canned tuna in tomato sauce, bread, French fries, and omelets. Lisa and I then accompanied Guilain and Daniel and Alex to ONAT to work out a payment procedure for the second week. Daniel took us to see the traditional blacksmith in his little shop on a side street. He was at work, sitting cross-legged on the ground, filing notches in the slightly curved blade of some tool. Lisa bought a bracelet from him and I a small leather container of kohl. We looked in the two other craft shops, and Lisa purchased some jewelry and I a traditional (but new) lock in the more sophisticated of the two stores. The other shop was dirt-floored and disorganized and specialized in decorated leather-goods. There were a couple of old Tuareg camel saddles for sale, and a very nice mat ran around two walls of one of the two rooms. Next, we bought some oranges, bananas, pastries, and bottled water at various shops and stands. The hotel had just had a large party of guests the previous night, and following some of our group’s showering, the water supply was exhausted. So no showers or sock-washing for Lisa or me. We couldn’t even bucket-flush the toilets. No water would be obtainable until the next morning. We had dinner at the communal table in the "restaurant." The bed-sheets have holes and are too short to reach the ends of the bed. At some time during the wee, small hours, dogs began to bark in town and the rest of our party arrived in the hotel corridor. After the openings and closings of doors finally died down, it was not too long until the amplified call to prayer was being belted out from the mosque—it must have been 4:00 A.M. There was water running in the sanitary annex this morning, but we didn’t take time to brave the smell and to shower. After breakfast, Lisa and I walked to the African market and wandered the booths. There were lots of local-style but imported clothing and yard goods, but also everything from cheap furniture to cell phones. I purchased a substantial coil of goat-hair cord—other than decorated-leather sandals, one of the few things we saw representing local crafts. Four additional participants (last night’s arrivals) joined us this morning: Günter Welz and Verena Jung from near Stuttgart, Germany, Ray Millar from near Birmingham, England, and Cary Tinley from Indiana. We walked down from the hotel to the main street to find the vehicles that would transport us on the day’s excursion. It took a long time to get organized, but we were off by 10:30. I saw a black bird with white outer tail feathers. We came to a road junction outside of town and paused for some reason. There was an abandoned water skin by the road; I salvaged the goat-hair carrying cord. Some Tuareg are said to be running their herds in this area; there is an unusual quantity of (mostly dried-out) grass on the dunes this year. After approaching some rocky hills, we took off on a track in the orange-buff sand, passed through a little pass, and climbed a dune to where there was a hazy but impressive view across a great sweep of sand to knobs and buttes of stratified dark-gray rock—vaguely reminiscent of Monument Valley.

We parked in the shade of a rock knob to take lunch. The buttes, called Timras ("Molars"), were visible in the middle distance, their bases hidden by an intervening dune. In front of that was a lone dark acacia tree. This is known as the Tikoubaouine area. We drove up a canyon to a large opening (ca. 20 meters/66 feet high), Tikoubaouine Arch (ALG-5), with a little opening above it and a small sand dune visible through it [see photo at top of this page]. Then on to a second arch, Touia Arch (ALG-2), high in a canyon-wall spur. While others climbed up to get a better view, Lisa and I went off a little way and sat on a ledge by ourselves. A third arch was Agelman Arch (ALG-3). Other arches are seen here and there as we go along.

Coming out from the last arch, we obtained a great, if hazy view of buttes and a pointed pinnacle. Back near the first arch mentioned in the previous paragraph, we stopped to photograph a balanced rock similar to those along the road to Lees Ferry, Arizona, and the adjacent landscape of dark rock lumps and bright sweeping sand. There were some dromedary rock paintings nearby. A party of hikers passed through.

Amazing yellow flower heads resembling huge asparagus tips emerge from the sand here and there; there is no visible foliage. On the way out, we passed a small nomad caravan of loaded donkeys and walking men and women. A mile or so behind, herders followed with a scattered herd of goats. We returned to the paved highway and commenced driving toward Djanet. On a slope to the right of the road was an ancient tomb, consisting of a central low stone-covered tumulus, two low concentric rings of piled rock, and what may have been two more stone mounds at the lower margin. Coming out on a very broad flat, after a few miles we turned to the right onto it and raced across it at 75 kilometers (47 miles) an hour, after a few miles arriving at the foot of the first dunes of the Erg Admer, a sea of sand rising to high, sharp-crested mountains. We walked up the fairly firmly packed slope to the westward. To the south was a barchan-shaped ridge of sand, and everything was delicately decorated with ripple marks. A long-legged black beetle made lacy tracks in the surface. The whole scene was very serene.

I demonstrated sand-swimming down a steep slope.

As we returned to the highway, the round sun was setting behind the dunes. A few miles short of Djanet, the left front tire blew, and we had to change it in the gathering dusk. Back at the hotel, we got ready for our first shower in a week but found that the pressure was so low that there was no water. However, the hotel manager arranged for us to descend into town and take showers in a three-stall shower room at another hotel. It was refreshing. We had a good dinner, featuring wheat berries and stewed vegetables, plus the inevitable dates and yoghurt for dessert. The hotel man is from a coastal town and has been in the hotel business only a couple of years. He seems a gentle soul and is concerned with the short-sighted and materialist approaches that are leading to excessive groundwater withdrawal and to global warming. His family is in book and magazine printing, which he tried but didn’t stick with. Before entering the hospitality trade, he was a videographer/cinematographer. Most houses in town have running water, but only from 7:00 to 11:00 A.M.; they must store water for later in the day. Day 9: Feb. 27, Djanet and Tadrart We were awakened by the pre-dawn call to prayer, assisted by barking dogs. The water was on in the annex, but the toilet in our building was stopped up. After breakfast, the newcomers had to go to the bank and to ONAT, so Lisa, Lola, Alene, Dagmar, and I walked to the African market; most of the proprietors seem to be Arab. We found one craft stand but bought nothing. Lisa purchased a shawl at a clothing booth. Some women’s shawls are made in Turkey; some cloth comes from Dubai. On the return to town, we stopped by the forgeron’s, and the ladies bought some jewelry, which is much less expensive than in the crafts shop. He had a goatskin bellows attached to a pipe to the hearth. He sat cross-legged on the dirt floor. There were several camel saddles he claimed to have made and colorful leather camel bags with elaborate decoration.

Then to the bank and ONAT to see that the newcomers were getting along. When they were finished, we climbed the stairway to the hotel. Most of the vehicles had arrived, but one was late, so we didn’t get off until 10:00. We drove southwestward and then eastward on the Libya highway. After an hour and a half, we passed a herd of camels and then went through a valley bounded by bare exfoliating rounded granite bluffs. After a while, sandstone caprock crowned the granite slopes, and acacia trees appeared on the broad, flat valley floor. We stopped at noon to have lunch beneath acacias. A lot of what I call sand melons—about tennis-ball sized—occurred in patches, and a mock game of boules was quickly gotten up. These fruits are said to be very bitter but are eaten by donkeys and wild animals. Wild melons are colocants in French, alqot in Tuareg. The acacias have tiny green compound leaves and long, sharp thorns like porcupine quills.

The highway was now unpaved. At a wadi, we took off to the right toward a line of cliffs, the Tadrart. For a while, we passed through a sort of badlands area of thin-bedded material. We entered the mouth of the canyon of Oued In-Djerane and drove up some miles. The cliffs here are somewhat smoother and lighter in color than those of the Tassili and the landscape reminded me of lower Grand Canyon. There was an interesting arch in a high projection to the right. We did not have time to get to it, and it remains uncataloged.

We set up camp in a rock-bound amphitheater, and found a site on sand in a relatively sheltered

angle; there was a breeze that could quickly have carried our tent away had we not anchored the

corners with heavy rocks in little "sea anchors" made for the purpose.

Lisa and I climbed up the ledges to a bench that afforded a sweeping view up canyon and to crags illuminated softly in the last rays of the setting sun. Among the scattered rocks of this region are tabular stones of cordovan color that produce streaks ranging from red-orange to dark-red. I assume that they represent the source of pigment for the various red tones seen in rock art. The Tuaregs say that powder from such rocks is used by their women as cheek rouge and, mixed with indigo, for lip coloring. Some of the drivers keep a sheath knife on the shelf above the dashboard. Often, a talisman hangs down from the rear-view mirror. Our driver Ibrahim’s rear-view mirror has a bit of fennec skin and fur hanging from it as a good-luck charm. After breakfast, we walked up to the head of the side canyon of which our campsite is an annex, and climbed up the rocks. Halfway up, one looks down onto a guelta, that of Tiseteka, with a fair-sized pool. There is a short, sinuous slot canyon. Climbing higher, we passed a large, round dry pothole, like an oubliette. We walked under a good-sized bridge spanning the drainage and saw a unique second bridge in front of the dry fall, a large flying-buttress type of span, the lower part of the free end being pierced by a second, vertical opening. In a major rainstorm, a big waterfall comes down the canyon head, fills up a large plunge pool, flows through both the main bridge and the smaller one, continues under the next bridge and into another big, deep plunge pool, whence it flows on down the drainage. These are termed the Dryfall Bridges of Tiseteka (ALG-281 and ALG-282). More photos of this spectacular bridge are below and two more of Guilain's photos are also here.

On a bench well above the rim of the slot canyon, there is a substantial cave in the parallel left-bank cliff. The front part of this cave is actually an uncataloged natural bridge, separated from the cliff by an enlarged joint a few feet wide. There is even a small arch through one end of this bridge, making it a double opening. There are lots of bird droppings. High on a shadowed side wall of the cave is what looked to be a large, oblong prepared surface, into which are incised parallel vertical lines, but it was not clear whether these were natural or artifactual. Further, up on the bench was a small spur with two moderate-sized openings. Arch city! Guilain calls this group Dryfall Arches of Tiseteka (ALG-416).

Behind the last two of these arches is an incised sign like the donkeys’ brands. Akhnini said it’s the sign of a Tuareg political confederation that made peace with the French when they first occupied the region in the 1920s. His people didn’t belong and never made peace with the occupiers. As we walked out, a flock of pigeons flew by, presumably heading for the guelta.

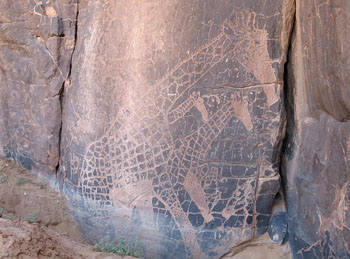

We continued driving up the canyon, pausing to look at rock-art panels. One had modest-sized

painted cattle and other animals, but the others featured large pecked elephants and giraffes,

seemingly reflecting some understanding of perspective, with parts of smaller, farther-away animals

covered by overlapping larger, closer ones. Alluvium had buried the lower part of the panel, and an

excavation had been made to expose it. One large collection featured sizable engraved pachyderms.

One of the giraffe sites also had inscriptions in Tifinagh, which one of the drivers said is in an

uninterpretable archaic language.

We took time to go up a side drainage and explore two little gorges. The first was notable mainly for a couple of blackened conglomeratic deposits near its mouth consisting of quite sizable cobbles. The other, main gorge was a joint-determined slot canyon a couple of feet wide with mostly straight, sheer walls but also a few rounded widenings. We all were reminded of Utah. One slot had a small natural bridge (ALG-280). We passed several arches, and came to a point in the wide wadi from which we could see a broad row of three large vertical openings, the Three Arches of Tamezguina (ALG-277, ALG-278, and ALG-279). We stopped for lunch not far beyond these. There were many flies. Ibrahim said that the flies are seasonal. They emerge when it warms up at the end of February. The fly season lasts for four months.

There was a knob of rock behind the picnic site that has an enlarged-joint opening, and one could frame one of the real arches through it. There are scattered acacia trees down the valley. Lola and I each found dentate sherds. Günter laser-measured the height of the large arch, Tamezguina Arch 2 (ALG-278), at 45 meters (148 feet). Some of the group saw an eagle flying over, harassed by a corvid. We later heard a call that might have been the eagle's.

After the sun went down, Lisa and I walked over to the large arch and climbed rocky rubble into its

enormous opening. The view toward camp was beautiful, as was the one away to the north, one of

sweeping orange sand and contrasting gray-buff bounding bluffs and isolated knobs.

Back at camp, someone had brought back one of the giant false asparaguses, which are edible but very bitter [Lhote 1959:140]. Apparently, the Tuareg cook the root in the coals; it’s supposed to be good for diabetes. If we were served any of it, it must have been in the stew. At dinner, much of the talk among the guides was in Arabic, with a few French words thrown in. After dinner was over and Tuareg tea being served, Mustafa Ibba, 35, one of the drivers, called me over and told me (in French) that he had a lot to say to me. I replied, "I’m listening." He asked if Lola were married. I said she wasn’t. He said he’d like to suggest a Tuareg-American marriage and merger. So, I translated to the assembly that I was now a marriage broker and was advocating this handsome young man with a good sense of humor. She basically said, "Thanks, but no thanks." I repeated his virtues, pointed out that he spoke three languages, but also mentioned that Lola had no camel as a dowry. But he countered that he had not only a camel but goats and donkeys, too, and that he would bring these to the marriage and had a tent as well. Someone said that Lola had a tent, and he said something equivalent to "Your tent or mine?" Mustafa said that if she married him, he could get a visa but that she could come live here if she liked. She said that she’d miss her grandchildren, but he said they could come too. I asked him how many wives and concubines he already had, and he assured us that Lola would be the only one. I warned Mustafa that American women are very independent and not obedient, but he said that was OK. So, he continued, "How about it?" As Lola still demurred, despite my pointing out that she hadn’t had a better offer all week, he graciously offered to give her until the following morning to make up her mind. As Lisa and I left, Akhnini whispered that it wasn’t tea that Mustafa had been drinking. After breakfast, Lisa and I walked over to the arch [ALG-278] and I up into it to photograph the views. After packing up, some walked to the area of the arch. There was half of a metate lying on the ground. We had seen one in the Tassili as well. We saw jackal tracks and were told that nomads hunt gazelle and mouflon.

Driving on up the canyon, we passed a terrific rising dune and then stopped to see some

small-figure pictographs in red and buff, including humans, cattle, ostriches, and a lion. There

was a boulder metate. Farther up, on the opposite, left-bank side, is a boulder on which appear

large pecked petroglyphs. On one side is a herd of elephants, one defecating, and below the herd is

a line containing a multitude of small human figures, in three groups. The central figures look

like a school-recess group playing basketball.

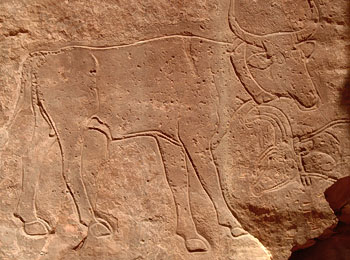

On the front side are large giraffes, but the illumination was unsuitable for photography. On the back side was an erotic scene. The guides joked that it depicted Mahamoud, a jaunty member of the team. As we went on up canyon, the rock walls became less prominent and dunes more so. At one point in the broad valley bottom, three out of the five quatre-quatres (4x4s) got stuck in fèche-fèche: soft sand in the wadi whose surface is deceptively hard (the sixth, cooks' vehicle, was not with us). So, a retreat was called, and we reversed direction. On the left bank a little way back down canyon was a sizable lump of rock on which were incised large zoomorphs, including cows and a rhino. Outstanding was a big bull, very well executed and with legs in perspective and wearing a collar. Inside the outline, the surface had been ground. There was another, lower, horned head, looking in the opposite direction. The accomplished drawing and quasi-bas-relief gave the rendering an Egyptian look. At the site, too, were a metate, half of a hammer stone, and a large sherd of very thick pottery, blackened on the interior side and with shallow indentations on the outer surface. An Italian party was also at the site.

We looked at one additional site with much cruder cattle and then headed over to a cove with a playa, for lunch. To the east were high, smooth, almost orange dunes with reefs of blackened rock sticking out of their sides in stark contrast. After lunch and a rest, some of us, at various times, hiked a mile or so over to a sharp-crested ridge of sand, behind which and in front of the high front of the erg was a playa and some dark prominences rising up—most notably, a silo-shaped monolith on a somewhat leaning base. In stone-studded areas nearby were many dentate potsherds. One or two rim sherds were decorated with cross indentations. Lola found a large piece of plain pottery.

We proceeded to another area with rocky outcrops and some small arches and a view of sculpted peaks of orange sand. I speculate that the oranger color of this erg reflects greater stability and therefore more continuous weathering, yielding iron oxide. Coming to a sort of pass, we stopped to see a large and handsome free-standing arch, In-Tehaq Arch (ALG-274). An unnamed arch (ALG-421) was nearby. The caravan traveled up a side drainage a mile or so to the campsite for the night. Off to the west, a thin cirrus sheet showed cloud iridescence. At dinner, Mustafa milked the marriage-with-Lola shtick some more, and Lola played along with friendly familiarity. The meal was the usual: we always had bread and soup with noodles or barley, and couscous or pasta with vegetables and scraps of mutton, and dates. There were mackerel cirrus clouds this morning, turned salmon by a not-yet-risen sun. I found a plain rim sherd at the camp. Daniel found a number of sherds, a couple incised, others plain and punctate, as well as three fragments of a metate. Daniel also found half a red-stone bracelet. One of the Tuaregs said women wore them on their wrists and men on the upper arm, to cut throats with if they got into a fight. We walked to In-Tehaq Arch, and the vehicles followed. We drove up valley from the arch, coming to an interesting 42-foot-high oblong opening at the end of a detached rock (Superpillar Arch, ALG-420). There is also an enlarged-joint side entrance. There is some crossbedding in this sandstone. There was now no direct sunlight, and David Parker, the English professional photographer, likes it that way; so, our vehicle stopped for him to take one of his 12-minute panoramic images. The next stop was for some small-scale rock art, probably of the Garamentes or Equine Period, that depicted horses and riders, cattle, and hunters. There was also some Tifinagh. As he drives, Ibrahim sings a Tuareg song concerning traveling with a herd of camels, people in front and behind, and how life and love develop on the journey. The tune is more Middle Eastern-sounding than what we’ve heard heretofore. He says tourism with vehicles began here in 1969. We are in a different drainage than we were yesterday, that of Oued Ouanagan. We drove up into a sort of broad amphitheater and then walked up a little ravine to see an arch that guide Salamou Ghali knew of, Tilafazo Arch (ALG-425). It is fair-sized, piercing a free-standing rock lump between two small drainages. A little grotto under one end went all the way through. Guilain and Daniel spent a good deal of time climbing a crag and finally succeeded in reaching an interesting double arch high on its side (Crag Arch, ALG-441). It appeared to be about 15 feet high. Lisa and I had gone part way up, and on the way down I spotted a circular piece of red stone. Nearby was half of a similar piece. The two fit together, and a half-inch-diameter biconical depression had been drilled from the two sides, creating a quarter-inch aperture. Clearly, someone had begun to manufacture a bracelet but the stone had split in the making. We drove on to a picnic spot. Near here, Daniel discovered an intact fragment of plain pottery representing perhaps about 20% of a vessel of a wide-mouthed, pointed-bottomed jar form. He also found many ostrich-egg shards. We had free time after the usual bread, salad, and oranges lunch, and some of us tramped across the valley to a pierced monolith that Guilain has dubbed "Hedgehog Arch." Atop a pedestal stood a smooth four-legged "creature" with a "snout" and a rough-stone back. It was quite cute. The far side had a flying buttress supporting it.

Lisa and I found a sheltered angle in a nearby rock lump and relaxed away from the crowd. I was sitting in sand and leaning against the cliff. Flies were attracted to us, and a little rock-toned lizard took note of the fact and ran up onto Lisa, who jumped up with a screech. It then approached me on the rock face, giving me the once-over, and then leaping atop my brimmed gabardine hat. It walked around on my lid for a while, and then returned to the rock. A bit later, it ambled over to my hand on the ground, zipped onto it briefly after a fly, and then retreated.

Tuaregs drink only at meals—mostly tea, it appears. For their sanitary functions, the less bashful just go a little way away, face away from others, and squat down in the privacy of their caftan. The quatre-quatres have their air intakes at the ends of pipes rising to roof height, to avoid sucking in sand. This morning, to start his engine, one of the drivers put a rag atop the air filter, took out a plastic bottle jammed into a cranny behind the left-hand headlight, and poured some fuel onto the rag. When the motor caught, the bottle was capped and put back in its niche. We had lunch at a place called Ouan ("Camp") Ekanesi. At 3:00, we moved on eastward toward the erg. Apparently, the sand is encroaching on the rocky country. The dunes are quite orange here. I have a new theory on the color. There are basal strata of coarse, dark-red sandstone that are pretty clearly the source of the red sand. The grains of the buff sand are notably finer than the red grains. Therefore, the wind removes the buff grains more readily, residually concentrating the red.

We set up camp toward the erg. Tonight, for the first time on this week’s trip, the Tuareg made tadjila bread, which, with a sauce, formed the main course. After the first serving, the cook always urges us to have un peu chouïa ("more"). Barbara was helped to put a chèche around her head. The Tuareg were amused, because the chèche is men’s wear.

Near this camp, Daniel found buried metates, part of a red-stone bracelet with decorative incisions on its edge, an ostrich-egg bead, and one thin stone bead. Teatime always precedes and succeeds lunch and supper, accompanied before meals by cookies. Evening cooking is done in the dark on a gas stove. How they can see to work is a mystery. According to Lola, one of the Tuaregs cleaned his hands by stripping somewhat aromatic leaves from a local bush that carried inverted-teardrop-shaped seedpods, rubbed the leaves in his hands, and then had her pour water over the hands. If the leaves are put into a container of water, the latter becomes "soapy." I was told that when there is cloud cover, it gets hot. The blanket of cloud impedes heat radiation from the ground. In confirmation, it was uncomfortably hot today, for the first time. There was some misunderstanding regarding Mustafa and Lola that created a bit of tension. It was only about a third overcast, and less hot. This area is called Tin Merzouga. The Tuareg personnel on this quatre-quatre part of the expedition seem racially more mixed—more Arab in some, more Black African in others—and somewhat less traditional than those with us on the Tassili plateau. We took off, passing by a monolith known as La Coupe du Monde (World Cup). [See this panoramic photo of Guilain pointing out Tadrart scenery not far from the World Cup. The photo was taken by Tom Budlong on a previous trip.] From there, we walked half a mile across the valley of the Oued Ouanagan, in what is called Le Cirque, to view a quite large high arch (World Cup Arch 1, ALG-423). Guilain climbed up to it and looked miniscule in it. A second opening is found in the same rock formation (World Cup Arch 2, ALG-424). There are many lesser openings in view.

In the oued were hundreds of wild melons, on vines radiating out from a center. We proceeded, passing yesterday’s luncheon place and stopping to examine two rock-art sites, one with camels and cattle, the other with cattle, some couchant. One was amazing, with bent-under foreleg and head turned back. Here, too, were bedrock pigment mortars and a longer basin into which water for mixing paint would have flowed via a crack. At another rock face farther along were large pecked giraffe petroglyphs, one reticulated. The following stop was to fill the water containers at a guelta, a green-colored plunge pool in the rocks. On the rock not far away were excellent petroglyphs of a pair of moving giraffes, with all four legs depicted. The realism, perspective, and fineness of execution surpass any other region’s rock art of which I am aware, although some in southern Africa could contend for comparison (cf. Willcox 1963; Garlake 1995).

Upon exiting from the side drainage containing the guelta, we passed, on the right, a large, rounded, undocumented arch cut through the upper part of a semi-detached bit of cliff spur. Continuing down the valley, we stopped again at Superpillar Arch (ALG-420), and then passed, at a distance, the big free-standing arch (In-Tehaq Arch, ALG-274). We drove into a big amphitheater with a playa, with high dunes of the erg on one side and a mix of dark rock and bright sand on the others. In the distance in one direction was an arch with a tall opening.

We passed the silo rock of the other day and continued a long way down canyon and into a side drainage for lunch. Up a rock ravine is a twisty canyonette. Guilain, Daniel, and I climbed up on the rocks where cairns marked a route. There are three very large potholes, the middle one half-full of water. It would have been necessary to lower containers on ropes to obtain any of the liquid. We lunched opposite the ravine. A few hundred yards up canyon is a decent undocumented arch in a fin projecting from the canyon wall. There is some pecked rock art in this vicinity: cattle, giraffes, and a nice ostrich. There are many, many camel droppings in the Tadrart. When the scheduled departure time rolled around, Guilain was up in an interesting skyline arch. The vehicles started without him but stopped opposite where he was. He exhibited reluctance to descend, and when he did he was angry with Ghali for having started without Guilain’s say-so. [Although we have no photo, Guilain dubbed it Mesa Arch and reports a GPS of 32R 688630 2662267 and a measured span of 12.2 meters. He also says the view of In-Djerane Canyon from the arch is thrilling.] We drove for some distance down canyon, which was scenically quite attractive, and near the night’s camp we took a look at an undocumented cave arch that contained some nice pictographs, including cattle and sheep. There was also one that we were told was a Garamentes chariot, although this was not obvious. The camp was up a side drainage, and Lisa and I found a nice secluded tent site between a dune and a rocky slope. I persuaded the guides to sing around the campfire after supper. They had some trouble finding songs they all knew but did manage a few numbers, to the accompaniment of jerrican drumming. My impression was that they had gotten some of the songs from CDs. Day 14: March 4, Tadrart, Tegharghart, Djanet We moved on down the canyon and then stopped to see some rock art. There was a big reticulated giraffe petroglyph and small dynamic red figures and, a bit down canyon, a lovely painted giraffe, with one foreleg extended and the other bent under the chest. Outside the shelter was a huge round and deep water basin carved into a boulder. The trace of a sidewinding snake was prominent on the sand floor of the shelter. As we exited the canyon, we passed four camels. Ibrahim says only a very few Tuareg live in areas with enough verdure to support cattle. We returned through the argillaceous badlands to the Libya highway and went in the direction of Djanet. Back in the granite country, a lone knob rose out of a broad playa. Its surface was covered with broken blocks of rock, upon many of which had been pecked petroglyphs, said to be of the earliest period. Some are heavily patinated, but others less so and may be copies of, or renewals of, the older ones, and include cows. The oldest forms incorporate, especially, concentric circles and double spirals, and are reminiscent of British Isles and Breton megalithic carvings [cf. Twohig 1981]. This knob must have been an island when there was a lake here, possibly accessible only by boat. It gives a very broad prospect. Three military helicopters flew over, the first aircraft we had seen or heard. We took a desert "shortcut" in the direction of the famous Weeping Cow petroglyph rather than following the paved highway. Lunch was taken under the dense shade of an acacia in the oued. The numerous knobs of broken granite around there carried skirts of coarse sand weathered from the rotting boulders. Daniel directed us across a ridge, whence we could see, at a considerable distance, a sizable heard of goats. The track down wadi and across extensive flats ultimately took us across the highway, beyond which sandy tracks led us to a lump of black rock, on a face of which is carved the utterly remarkable Weeping Cow, at Tegharghart. This is an intaglio composition of four large cattle, one of which has a mark below the eye that is interpreted as a tear. One cow’s body has patches, dark where the original patinated surface remains, lighter where the intaglio work has created depressions. The animals’ horns describe particularly elegant curves. We then returned to Djanet. There, we noticed the occasional woman carrying a burden on her head. The hotel man was beaming when we returned. He assured us that this time, there was water. It turned out that this mainly meant three large bucketsful, for washing and flushing. An assistant picked one up to carry it into the washroom, but the handle broke and the water spilled out on the ground. In fact, three people managed to wash with the last trickle from the showers. Others, including us, bought bottled water downtown and washed with it. Since I had no clean shirt, Lisa and I went to the African market and I purchased a North African-style pullover shirt with embroidery, which hung down almost to my knees. A pair of huge-waisted loose trousers came with it, but it was unclear how these would be held up.

Lisa and I stopped in at the local café for a cool soda. There are not enough chairs to provide seating at all the tables, so we had to scrounge a couple from neighboring occupied tables. The place was out of the peach-flavor soda we’d had a week earlier, so we had to make do with pineapple-flavor stuff. Ray came along and wanted a Coke, but they were all out, so he left. I took a little stroll down below before dinner, looking at gardens behind the palm-frond fences; here, these were strung between date-palm stumps. Crops that I could identify were wheat and potatoes. On date palms in one grove, equine skulls and jawbones had been hung on several trees, perhaps as anti-evil-eye protection. The other crops were in waffle gardens. Irrigation water comes in via pipes, debouches into diked ditches, and is distributed to the bunded garden plots. Some rows of plants have low bunds separating them. I saw some penned animals that looked like goats, although a local man called them sheep. They were not wooly, and had dark-brown hair or were piebald brown-and-white. They had floppy ears, and the ram spike horns; he also had a pair of dewlaps hanging from his neck. We had the usual sort of dinner at the hotel, with a few words from Guilain, whom we thanked for his great efforts. Then we rested in our rooms until midnight, at which point our drivers conducted us to the airport.

The plane from Paris was late, and, with customs and security, it was 4:00 A.M. before we

boarded.

Stephen C. Jett, a charter member of NABS, is professor emeritus of Geography and of Textiles and Clothing, University of California, Davis, and now resides in Abingdon, Virginia. He edits a scholarly journal and has published extensively on the American Southwest, especially on the Navajo. Jett is an authority on Rainbow Natural Bridge. He was the first to record a number of natural openings, including Jett Arch, off Lake Powell, which he named for his father.

Cailleux, Sebastien. 2006. Tassili: Le plus grand musée du monde, à ciel ouvert. . . . [Tassili: The World’s Greatest Open-Air Museum]. Aigle Azure Magazine 9:38-41.

Debossens, Guilain. 2004-2006. The Natural Arches of Tassili National Park. Descotes-Toyosaki, Alissa. 2006. Djanet: Une oasis, des déserts [Djanet: One Oasis, Several Deserts]. Aigle Azure Magazine 9:32-37. Garlake, Peter. 1995. The Hunter’s Vision: The Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. London: British Museum Press. Lhote, Henri. 1959. The Search for the Tassili Frescos: The Story of the Prehistoric Rock-Paintings of the Sahara. New York: E. P. Dutton. [tr. from the French by Alan Houghton Broderick] Twohig, Elizabeth Shee. 1981. The Megalithic Art of Western Europe. New York: Clarenden Press, Oxford University Press. Willcox, A. R. 1963. The Rock Art of South Africa. Johannesburg: Thomas Nelson and Sons.

LINKS

For another detailed description of a trip to Tassili (in Italian, with many photos), see |

|

|

|

Index Page

|

|

First Arch ALG-66

|

|